Close-up: the cameraman enters the frame, changing the standard lens to a telephoto lens. He pans the camera to its side and continues filming the subject. This sequence is one of many in the documentary Man With A Movie Camera (Verkov, 1929) where the filmmaker is visible in the filmmaking process distinguishing the film as an early example of the Reflexive Mode of documentary. Making the audience aware of the film’s process is a standard in the Reflexive Mode, allowing an honest and truthful portrayal of a subject (Nichols, 3). Since then, filmmakers have made a reflection on their subjects through this mode, but some used the Reflexive Mode to make a reflection on themselves, thus exploring the personal documentary. George Semsel explains the importance of personal documentary in Notes from a Journal. He states, “You cannot make a film which can effectively alter the world until you have really looked at yourself and made an honest, forthright evaluation”. The trend of personal cinema began with Richard Hancox in the 1980’s as he encouraged personal documentary and motivated his students to “investigate questions of time, memory landscape and documentary convention” (Cole, 6). One student who emerged from Hancox’s schooling was Toronto native, Alan Zweig. Using the modes and conventions of the Reflexive Mode, Zweig makes a candid evaluation of himself, late in his career, in a trilogy of films (recognized as the Mirror Trilogy): Vinyl (2000), I, Curmudgeon (2004), and Lovable (2007). Showing truth to Semsel’s thoughts of personal documentary, Zweig’s Mirror Trilogy allows him to make an honest evaluation of others outside his reality in A Hard Name (2009).

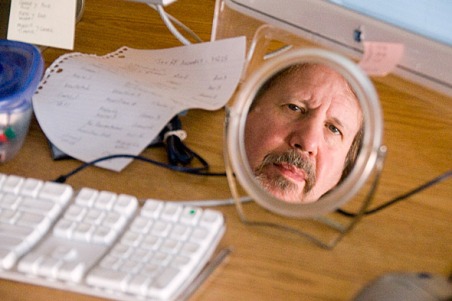

In Alan Zweig’s Vinyl, the first film within the aptly named Mirror Trilogy, he focuses on record collectors and their huge collections. Zweig tries to go deep within the psychology of the collectors to discover the reasoning behind the big collections. He often inquires them about their collections, trying to deduce why anyone would continue on with such an over abundance of records within their domestic residence. In between his interviews with the record collectors, he monologues to a mirror, talking about his own experiences with record collecting and sharing anecdotes and personal stories, some of which are occurring at that moment. In reference to mice being found in his laundry:

“It was like it was saying: “Hey! Give up. Doesn’t matter, clean up, change your life, doesn’t matter we’re gonna be there… sullying everything, making everything seem like crap, all your efforts”.

(Alan Zweig in Vinyl)

The viewer is introduced to a very interesting cast of characters throughout the documentary. One man wants to collect every single record that exists, while another has half a million records in his house, filling up his entire cellar and even his bathroom. One man, after surviving testicular cancer, went to collecting to cheer him up, and another lost half his collection to his ex-wife in a divorce.

As the documentary progresses, the viewer really gets a feel for each person and an understanding to their desire of records. One collector describes that feeling of magic upon discovering a song he’s never heard and another describes the thrill of being at a record store and searching through albums. However, most of the collectors and even Zweig had noted that it’s not just about the music, for some it was (they would collect because they enjoyed the music), for others, it was an obsession. Just as a nail biter would keep biting his/her nails as a form of “grooming”, the record collector will keep buying records as his/her form of “grooming”, even if they do not necessarily need the record, it is that feeling of satisfaction that drives them. A moment happens to Zweig, where he buys a stack of old Jewish records, stating he does not need them but he cannot just leave them there – it is like a siren call. One man describes the obsession to collect as a form of psychological illness, whereas unresolved problems from a person’s life can lead them to collect as a way of compensating for that.

As the documentary progresses the viewer quickly realizes Zweig’s intentions, he seems to want to find an answer as to why he is single with no kids. He feels his collecting is the leading cause of this problem in his life and, through the film, is trying to have that theory validated. He often questions the collectors about their personal and romantic lives and always acts shocked when he hears that one of them has a girlfriend, stating it must be incredibly difficult due to all the time it takes to be a collector, as if the prospect of a romantic relationship just cannot happen due to collecting. The viewer gets a closer look at his sad life and his yearning for a wife and family as he tries to discover the real reason for being single. This common theme also appears in his second film, I, Curmudgeon.

I, Curmudgeon is the second film in Zweig’s personal Mirror Trilogy, which offers another insight on the filmmaker – his bad-tempered, disagreeable, and stubborn personality. In the film, he reveals the irritable nature of his personality with the reflection from a mirror, which is explained in three categories:

“Popular culture and all its crap, category 1. Category 2 is how my life did not go the way I wanted it to. Category 3 is man’s inhumanity to man, lack of charity, lack of kindness, lying, phoniness, cowardliness, all the stupid things done in the name of religion and patriotism, war, pestilence, violence, and mistreatment, and pollution, alienation, stupid, stupid people, all the horrible things in the world”.

(Alan Zweig in I, Curmudgeon)

Zweig describes his life as a three-act division where he finds himself growing bitter in the second act of his life, when he was in his twenties. At this time, his filmmaking career was not successful, a passion that developed at the end of his first-act. When others started calling him a curmudgeon in his thirties, Zweig thought it was the world around him causing this. As he was about to quit his filmmaking aspirations, he got lucky, thus starting the third act of his life where he tries to figure out the fallout and resolution to his negativity. This is an issue Zweig deals with the cast of curmudgeons as he provides an insightful study of their lives.

From the personalities Zweig used in the film, a few were recognizable figures – comedian Scott Thomson, authors Cintra Wilson and Fran Lebowitz, and comic book writer Harvey Pekar who also appeared in Vinyl. The others are ordinary, everyday people with a unique story to tell that all communicate their pessimistic character. Stories range from personal anecdotes to discussions with Zweig who is evidently in the room with them behind the camera. Some describe small but significant stories. If someone extensively describes his or her great and successful life, he’ll be happy on the outside but inside he’s saying, “Go f—- yourself”. Or if someone says, “Hey, lets go see this movie”, he’ll say, “Nah, it’s a piece a crap” or if one says, “Nice weather”, he’ll reply, “It could be better”. The same person defined his negativity as a smart-ass quality rather than depressive, and points out that there is difference. Zweig demonstrates this as well with his selection of personalities. Some will show a heavy frown while others will have a smirk or a smile.

Zweig makes appearances from the reflection of a mirror also telling us anecdotes from his life to track the sources of his personality. He describes an event where his friends spoke about a sneaker commercial that they really enjoyed where Zweig was the one thinking it was terrible and expressed this truthfully. While he was serious about his opinion, others felt pity and told him the little value of that commercial. Even one of the cast members told Zweig that he took it too seriously, and his friends were right. This also demonstrates the therapeutic, and analytical discussions between Zweig and his fellow curmudgeons.

Zweig closes the documentary with ideas relating to the theme of love. He introduces this with a story about his smoking habits. Smoking was a way to relieve his negativity to others with a big puff of smoke to their face. When quitting, he had to find other ways to express this. Subtly, he advises, “If a women says I hope you’re not quitting for me – it means she’s out [knows she won’t be in the relationship much longer]”. When a man confronts Zweig asking about his level of happiness, he replies, “two… two-and-three-quarters if I had a girlfriend”. Zweig continues, ultimately providing a fitting end to I, Curmudeon by confessing his biggest problem: “I’m not happy, I’m alone”. Zweig directs his love dilemma to the final chapter of his Mirror Trilogy, Lovable.

The common theme is most apparent within Alan Zweig’s Lovable, the third and final installment of the Mirror Trilogy. In it Zweig interviews single women with the intention of discovering the reason for them being single. The viewer is presented to a lovely group of women, all attractive with great personalities, who, despite their best efforts, still manage to remain single. Throughout the film, the women continuously try to understand it themselves, often expressing their frustration and just trying to find an answer to the question: “what is wrong with me?” The women come up with various theories to this question. One believes her aura presents a feeling of “I don’t need a man”, another believes there is the possibility she just is not marriageable and another who felt she lost her chance by not staying with a high school sweetheart (she considered staying with one as archaic). Sadly, it does not end there; most of the women are heavily affected by their single lives. One woman finds it difficult to stay occupied being single, another women’s grandmother was easily willing to give up a tea set she was saving for her granddaughter’s wedding, that’s how little faith she had in her granddaughter finding a husband, another has breakdowns just seeing regular couples and another contacts old boyfriends when she’s ovulating to fill that void in her life.

In between interviews with these women, Zweig reflects upon his own single-hood. He mentions his favorite activity as sitting at a café, watching the people go by, especially the women. Occasionally, a woman would go by and he would think to himself, “What would my future be like with her?”. Zweig, also, describes a great amount of dates that he went on throughout the documentary, most ending really badly. One date, he had mentioned to the girl the great chemistry they had and she replied, “Well that’s too bad”, and another broke up with him because of her many experiences of short relationships, which she felt would repeat with Zweig. He continues on dates hoping to find the one during the filming of the documentary, so there can be a happy ending. Sadly, that is not the case as near the end of the film he explicitly says, “I give up”. This ending really hits hard as throughout the documentary Zweig describes this undying want to have a wife and kids. This want had become so deep for Zweig he would end a relationship for the sole reason that a kid was not desired. He had not truly felt that gap in his life until a friend told him that he “Wants to have a full life, to experience everything within reason that life has to offer” (Friend by Zweig in Lovable). This was a defining moment for Zweig as this absence of a family he had barely felt before had blown up to great proportions. He stated that when searching on dating sites, he does not look for someone who seems fun or pretty, but someone who he could spend his life with (which, has not worked in his favor). This need is so big for Zweig that he acts completely shocked when a woman actually says she is perfectly happy being alone and in fact, enjoys it. Zweig seems to be completely baffled at the fact that someone can be content with the idea of being alone. Zweig ends the documentary by stating he will still be searching and believes it to be self-destructive yet hopeful, quoting a song “I believe my dreams may still come true, someday you’ll show me they really want me to. Gee whiz, that’s not the way it is, but that’s my favorite dream”, ending the documentary on a bittersweet note.

The Mirror Trilogy, unofficially referred to as the “Trilogy of Narcissism” (Michael, 1), although set with different subjects and opinions, it is all dealt in the same reflexive way. Most evidently, Zweig uses mirrors to reflect upon his views and personal life. Although, the mirror seems to be an obvious metaphor to the reflexive mode and his self-reflexivity he’s portraying in his documentaries, it works as a simple and effective tool. The mirrors put him in a vulnerable position that allows him to express his emotions sincerely to the camera (Michael, 1). The way his mirror shots are framed, in terms of mise-en-scene, are also reflective of his personality and emotions that he felt during that stage of his life and at that specific moment as well. For example, in I, Curmudgeon, one of his mirror set-ups include a book titled “Tell me About Chanukah”, a bah-mitzvah story prayer book, reflecting his Jewish heritage. In another mirror shot, he includes his cab driver’s identification card, reflecting his early life as an unsuccessful filmmaker before the Mirror Trilogy. In Vinyl, various vinyl records are often seen around the mirror in his mirror shots. The records often reflect either a mood he is feeling or relates to the story he is telling, for example a Curtis Mayfield album is shown while he talks about his experiences collecting Curtis Mayfield albums. The same occurs within Lovable, where most of the vinyls shown have a feminine or female figure on the album cover. Some of the last mirror sequences in the trilogy, seen in Lovable, involve Zweig cleaning his mirrors, a possible metaphor for him cleaning up his life in the aftermath of the trilogy. The most obvious aspect of the mirror shots seen in all three films is the presence of the camera.

The presence of the camera within the mirror shots is one of the defining characteristics that define this trilogy within the reflexive mode of documentary, making the viewer aware of the film’s process. Even during the interviews, the camera and Zweig himself can often be seen reflected in windows in the background. Sometimes, Zweig is also seen manipulating the camera. For example, in I, Curmudgeon, one of the personalities asks Zweig if he can zoom in to get a medium shot. Zweig agrees and does the change. In other modes of documentary filmmaking this scene would usually be cut out in the editing process, but Zweig includes it, maintaining the true nature of his work. This occurs, as well, at the beginning of Vinyl, where the first thing the viewer sees is Zweig fixing the camera to frame himself in the mirror. With the evident jump cuts, camera work and on-screen microphones, the viewer is left with an informal style of work. Subsequently, this style translates into his interviews.

His style of interview is anecdotal; it feels like a therapy session whereas the interviewees have an unscripted and natural essence to their dialogue. Not only is this helpful for the interviewee but important for Zweig as well, as he tries to reflect upon his similar problems. As he mentioned in a TVO interview, he does not meet up with his interviewees before the interviews. He sets up his camera within five minutes and starts recording as soon as it is set. He described his way of interviewing as spontaneous; he has no agenda nor a list of questions, he lets it happen. As Zweig says in the same interview, “When other people do their research… I shoot my research” (Zweig, TVO). This form of filming allows for a deeper connection with the interviewees. As Zweig stated for the TVO website, “For me a good documentary story is anything that has a whiff of honesty or authenticity about it… Humanity will shine through the screen” (Zweig, TVO). This very thing occurs with each and every individual interviewed. The interviewees are relatable people and through their humanity leave the viewer wanting to know more about them. Zweig does not involve a whole crew to do his interviews, it is only him and his camera, allowing there to be more intimacy between him and the interviewee. As one interviewee said, “Being interviewed by Alan certainly gave me the feeling of being a bug under a microscope because the personal nature of his inquiry brought me to a new level of self-reflection” (Cole, 4). Michael Cartmell, filmmaker and participant in I, Curmudgeon also complimented Zweig’s ability to talk anecdotally and “and [to] do so coherently, humorously, touchingly. This is his master trait; it’s who he is, as far as I’m concerned” (Cole, 2). The relationship between Zweig and the people, along with all the technical qualities involved, is the most common characteristic that translates into Zweig’s most ambitious project A Hard Name.

With Zweig’s personal, self-analytical work in the Mirror Trilogy, he was able to grow as a filmmaker and a person. Zweig was able to make a forthright, truthful evaluation of himself in the Mirror Trilogy, therefore allowing him to make an honest observation on a deeper subject with different personalities than himself. Following George Semsel’s ideals on the personal documentary, Zweig focused on his next film, A Hard Name, a film about eight middle-aged ex-convicts and their struggle to live normal lives. It follows the same reflexive approach he took with the Mirror Trilogy but he focuses on the ex-convicts rather than himself. His usual mirror set-up is not included but Zweig’s presence is still felt because his voice is heard from the sincere, therapeutic conversations he has with the people. The development of Zweig’s career and personal life is evident from the success of A Hard Name and the long road it took for him to get there with the Mirror Trilogy. A Hard Name deservingly earned Zweig a Genie Award, honoring him as a successful Canadian director and since then has started a successful family of his own (Pevere, 2). This perhaps extends his three-act-structured life to four – the fourth being fatherhood.

Zweig’s efforts, put into his most successful film A Hard Name, would not have been possible if it were not for his journey of self-reflexivity, seen in the Mirror Trilogy, which is made up of Vinyl, I, Curmudgeon and Lovable. In order to truly make a film about the humanity of people, he had to understand his own humanity first. His look into himself, be it his obsession with record collecting, his negative, curmudgeous ways or his investigative search into the truth behind bachelorhood, allowed him to create a film that could represent the humanity of others as if they were himself. Along with his unique filmmaking style and his knowledge of documentary, from an education provided by Hancox, Zweig was able to truly create films with heart. As George Semsel stated in Notes From a Journal, “Film, like education, comes out of the heart: one teaches because one loves and so one makes films”. Through his love of film, Zweig has taught us all lessons in humanity that one will never forget.

Bibliography

A Hard Name. Dir. Alan Zweig. 2009. Online.

“Alan Zweig.” TVO. Web. 8 Dec. 2012.

http//docstudio.tvo.org/story/alan-zweig

Cole, “Focus on Alan Zweig: The Curmudgeon Turns Lovable,” Point of View, No. 82 (Summer, 2011), 4-8.

“Hot Docs Q and A on A Hard Name with Alan Zweig and Others.” TVO. Web. 8 Dec. 2012.

http//ww3.tvo.org/video/166737/hot-docs-q-and-hard-name-alan-zweig-and-others

I, Curmudgeon. Dir. Alan Zweig. 2004. Online.

Lovable. Dir. Alan Zweig. 2007. Online.

Man With A Movie Camera. Dir. Diza Vertov. 1929. Online.

Michael, Joseph. “Behind the Doc: Alan Zweig.” BlogTO RSS. Web. 8 Dec. 2012.

http//www.blogto.com/film/2009/behind_the_doc_alan_zweig/

Nicols, Bill. “Modes of Documentary.” Web. 8 Dec. 2012.

http://www.godnose.co.uk/downloads/alevel/documentary/

Pevere, Geoff. “Alan Zweig, the Man in the Mirror.” Toronto.com Web. 10 Dec. 2012.

http//www.toronto.com/article/683007

Semsel, George, “Notes from a Journal,” (condensed by Hancox), unpublished, 1976, 1-2.

Vinyl. Dir. Alan Zweig. 2000. Online.