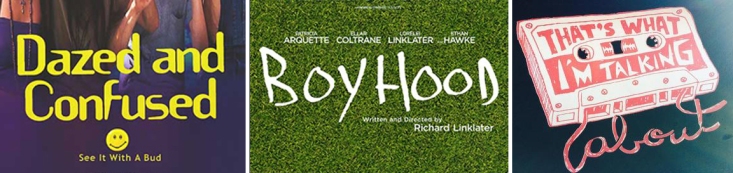

A New Richard Linklater Trilogy?

Could 2015 be witness to the completion of another Richard Linklater trilogy?

Linklater describes “That’s What I’m Talking About” as a continuation of “Boyhood” and a spiritual sequel to “Dazed and Confused”. There are elements and one interesting theory out there that connects “Boyhood” to “Dazed and Confused”:

JWR_4 on Reddit.com theorizes that Dalton, Mason Jr.’s college roommate, is the son of Cynthia and Wooderson from “Dazed and Confused”. Too expand on this, Dalton does have striking physical similarities to both “Dazed” characters. He is also both philosophical (like Cynthia) and laid-back and “cool” like Wooderson.

The liquor store clerk in “Boyhood” is the same as the one in “Dazed and Confused” who sold Mitch the six pack. On the surface, yes, it is the same actor (David Blackwell), but its the same character as well. I can tell by the accent and his character trait of giving advice to his customers. For example, in “Boyhood”, the man tells Randy ,”Take care of your dad now, son, you only got one”. In “Dazed”, he tells the woman, “Remember to eat a green thing everyday and have lots of calcium, it’s important for young mothers to have lots of calcium”.

Now no one has seen “That’s What I’m Talking About” but we have some information that can connect the film to “Boyhood” and “Dazed and Confused” already. The film is set in Texas and follows the lives of college freshmen in the 1980’s. Like “Boyhood” and “Dazed”, it is set in Texas and sounds like it can follow a theme of growing up and self-discovery. Linklater also mentions “That’s What I’m Talking About” picks up right where “Boyhood” ends (Goldberg 1). The characters in all three films will discover themselves in an important time of their lives. With similar themes of time and discovery, the setting of Texas, and youthful characters, can “Dazed and Confused”, “Boyhood” and “That’s What I’m Talking About” be considered a trilogy? I personally believe it could and if “That’s What I’m Talking About” is what I expect it be, I will proudly argue for this Richard Linklater trilogy in Best Trilogy debates.

What would you call this trilogy? Right now, off the top of my head, I would simply call it “the Linklater trilogy” – now that’s what I’m talkin’ about.

Sources:

Goldberg, Matt. http://collider.com/thats-what-im-talking-about-movie-boyhood/. Web.

The Birthplace of IMAX: An Expo 67 Retrospect

– – –

A research essay that uses an interview methodology to examine Montreal’s Expo 67’s role in the development of IMAX through the films Polar Life and Labyrinthe.

Author: Alberto D’Onofrio

– – –

On November 5, 2014, Montreal was witness to another IMAX premiere of a Hollywood blockbuster – Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar. As an enthusiastic cinephile, I attended one of the first IMAX screenings, while as a student of the medium, I sat quietly in the midst of the excited Montreal audience and asked myself, “Does anyone here know the role of their own city in the development of IMAX?” I wouldn’t expect many to know. Admittedly, there was a time I didn’t know myself until I took a class in University titled Advanced Topics in Film Studies: Expo 67. This is where I discovered that Montreal’s Expo 67 is the birthplace of IMAX. Expo 67 was a world fair exhibition held in the summer of 1967 with the theme of “Man and His World” where artists’ creative genius was put into place on works of paintings, sculptures, music, theater, dancing and motion picture (ExpoVoyages 1). Motion pictures, a medium that filmmakers experimented with in terms of style, format and exhibition, was part of the Expo’s intention to realize a future gaze. Roman Kroitor and Graeam Ferguson were part of the Expo 67‘s vast cast of filmmakers who’s work represented the future gaze and would be the eventual inventors of IMAX. Ferguson’s Polar Life and Kroitor’s Labyrinthe provided an experiential experience that included a precise and rigorous process that was not only appropriate for Expo 67 but an inception for the following years of developing IMAX, the world-renowned form of film exhibition.

An interview methodology that includes discussions with Ferguson, Kroitor and fellow co-workers (Toni Myers and Colin Low) will be used to understand their perspectives on the films that led to the development of IMAX. Interviews are particularly useful for getting the story behind a participant’s experiences and can pursue in-depth information around the topic (Mcnamarra 1999). Using the most common form of interviews of “people about specific historical periods or events in which they have participated” (Reuband 18), my study will be accompanied with an authentic perspective on Expo 67. While filmmakers are important to this analysis, an audience’s perspective on the world fair is also valuable to properly describe their cinematic experiences. Offering a touristic perspective, I will include excerpts from an interview with my cousin Antonello D’Onofrio. He was fortunate to experience the Expo at the age of ten – young enough to witness this future site with a childhood sense of wonder, yet old enough to remember the experience years later. Filmmakers created these works to immerse their audiences and they were equally important to the world exhibition. Participation by Ferguson, Kroitor, Myers, Low and D’Onofrio in this essay will offer a unique and personal outlook that would not be found in other methodologies.

Our understanding of Polar Life and Labyrinthe in relation to the aura of Expo 67 and IMAX’s development will also be discussed through theoretical discourses found in Andre Jansson’s “Encapsulations: The Production of a Future Gaze at Montreal’s Expo 67” and Alison Griffiths “Shivers Down Your Spine: Cinema, Museums, and the Immersive”. The precedent will be essential to examine selected statements from the interviews.

Bearing the theme “Man and his World”, Montreal was a city of the future during Expo 67 and pavilions of themes, corporations, and countries were built with this intention of a future utopia. Additionally, as writer Andre Jansson explains, “The future gaze was continuously worked out in tandem with other gazes, in particular the tourist gaze” (Jansson 420). The Expo used this model of design to elevate a tourist gaze of its visitors, to an extent that the Montreal citizens felt like tourists themselves. For instance, my cousin Antonello reminisces of feeling like an outsider in his own town because of the architecture’s hypermodernity. Besides the pavilions, a feature element of this world was the Minirail. At its basis, it was a transport system. Though most importantly, the futuristic monorail was applied as a scenic element that provided multiple perspectives of the utopia – similar to the films at Expo 67: “Whereas the Minirail moved people as viewers, Expo cinema immersed them in simulated mobility” (Jansson 429).

The filmmakers of Expo 67 intended to immerse an audience with their vision of the future in cinema. This came in a wide range of exhibitions from multi-screens, 70mm or 35mm film, to the creative use of water jets to form the screen in Canadian Kodak’s The Wonder of Photography (Journal of the STMPTE 196). Graeme Ferguson’s Polar Life was among these films at Expo 67. He acknowledged that, “There was a whole tradition of that [multi-screen] going back through the Expo’s in Europe and the American exhibit in Moscow” (Wise 18-19) which inspired Ferguson to make a new kind of movie theater where you felt like you were part of the movie (Zayas 1). Polar Life was exhibited in a circular theater that slowly rotated around its seated audience. Eleven fixed screens were placed behind a wall revealing different frames as it rotated through the open window (Lamont 4). Interestingly, Polar Life was initially made possible as a result of his IMAX partner Roman Kroitor. Ferguson recalls:

“Roman has asked me to consult for a day or two on Labyrinth when he was first conceiving that film. I had done a fair amount of filming in the Arctic and Alaska and so it wasn’t a startling idea, but I nothing particularly to show the committee, so I showed them The Love Goddesses, which couldn’t be a more remote film from what they were asking me to do. They said okay, “We’ll hire you to go and wander around the Arctic, but give us a film on the polar life” (Wise 18).

While the world fair was host to grand and imaginative film exhibits including Polar Life, Roman Kroitor’s Labyrinth was regarded as the most ambitious and expensive film at Expo 67 (Siskind 16).

Roman Kroitor was already known as a technical innovator for being one of the first filmmakers to use lightweight cameras in the 1950’s for his works of cinema-verite (Wise 21). He also co-directed Universe, an experiential film about space. Kroitor’s inventive and ambitious nature was fitting for Expo 67 and his film Labyrinthe reflected that. As the director explains:

“The original idea was to have seven theaters that the audience passed through. But when it came down to practicalities, we reduced it to three. We shot some footage with two 70mm cameras for the first theatre – one projected vertically at one end of the first chamber and one projected horizontally. The middle chamber turned into a light show and the third was a cruciform structure” (Wise 2).

Its exhibition was grand as the filming process. Kroitor recalls shooting on a camera rig that supported five synchronized Arriflex cameras (Wise 2) and Colin Low, one of the collaborators on the film, explains that Kroitor clamped a 35mm Arriflex to a helicopter to shoot aerial coverage of Montreal (Wise and Glassman 23). Despite its technical innovations in production and exhibition, Kroitor did not believe this was very innovative:

“What led to the creation of IMAX was the fact there were several big–screen things happening at Expo 67. Labyrinth was just one of them. Graeme Ferguson’s Polar Life was another. Chris Chapman did A Place to Stand and Francis Thompson did one for CP Rail, which was a six–screen film. What was very clear was that these big–screen images really knocked people out. It wasn’t just Labyrinth that put the bee in my bonnet” (Wise 31).

Furthermore, Labyrinthe included the combination of both 35mm and 70mm film. Though Colin Low explained, they weren’t the first to do so either: “They had tried it on a big screen with Cinerama in the 1950s, but we were really looking back to Abel Gance who shot Napoleon using three screens in the late 1920s” (Wise and Glassman 24).

As Roman Kroitor and Colin Low expressed, what filmmakers did in Expo 67 was not new, and theorist Alison Griffiths shares the same thought by writing, “This fascination with immersive, simulacral experiences of virtual environments is far from new” (Griffiths 81). Examples of these experiences include landscape paintings, magic lantern slides, and motion pictures such as Vitarama, the horizontal projection system in 1938 and its eventual successor, Cinerama. Griffiths includes early examples of immersive mediums to express that this technology, “Still positions it as constantly on the cusp of radical transformation in filmic experience” (Griffiths 81) meaning that it is always under investigation to expand. At Expo 67, the filmmakers explored new ways of expanding their knowledge of cinema with the intention of immersing through virtual travel and hyperrealism which has been a common theme in history. As panoramas and nickelodeons transported audiences on a journey, for minimal costs and without travel inconvenience (Griffiths 86-87), Polar Life and Labyrinthe did the same. Although applying different exhibition methods and content, Ferguson immersed his audience to the cold, yet familial Arctic and Kroitor provided its audience with a sensorial experience of beautifully photographed sequences. Eventually, Polar Life and Labyrinthe represented the birth of IMAX. Kroitor and Ferguson collaborated to develop their multi-screen technology after the world expo – an indication that cinema is “constantly on the cusp of radical transformation” (Griffiths 81).

In the interview with Antonello D’Onofrio, who attended Expo 67, I briefly mentioned that the expo inspired the creation of IMAX. While he did not know this, Antonello replied in an unsurprised manner knowing that what he was seeing at Expo 67 was a vision of the future. “It wasn’t just something to get us excited [for this one time event]”, D’Onofrio said, “but this is it, this is a preview of what’s going to happen [in the future]”. I can imagine that most audiences shared similar reactions and this response inspired Ferguson to develop this technology further:

“It was right after Expo [The development of IMAX] . I was up in Montreal in August, and Expo was very popular. It was obvious to us that there was a big audience. And it wasn’t just because it was multi–screen. It was because we had the screens bigger. Because we had more projectors to fill the bigger screens as well as the multi–images” (Wise 19).

Kroitor also saw the potential for this technology:

“What was clear to me was that you could create some interesting graphic and thematic connections using more than one image. I personally think that some day cinema will move in this direction. That was my main interest in developing IMAX, creating a system where this could happen” (Wise 31).

When Kroitor and Ferguson started developing IMAX after Expo 67, they agreed that while the films were successful, it was an inconvenient way to project them. This thought led to simplifying their idea to a large–format projector to fill a large screen with a horizontal, 70mm format – a method that is still found in IMAX today.

IMAX’s 70mm format remained a staple to its projection as did the medium’s encapsulation – to immerse an audience the same way Polar Life and Labyrinthe has. The Expo was, “Promoted as a new stage in development of cinema – even the future of cinema” (Jannson, 429) and witnessing its development since 1967, IMAX did prove the Expo’s vision true with sensory immersion still being a key component. An experiential experience remained an important element and technological breakthroughs in IMAX cameras made capturing extraordinary moments possible, such as, “Doing daredevil aerials in a small plane, exploring the oceans, experiencing space and life in zero-gravity, and being onstage with the Rolling Stones”. Toni Myers (co-worker on Polar Life) explains in 2009, “The [recent] invention of IMAX3D has provided a new, even more intense way to explore our surroundings and a challenging way to tell a story” (BMZ Staff 1). Alison Griffiths theoretical discourse continues to be true: while technology is due to expand to achieve greater accomplishments, the touristic gaze as developed in panoramas, and multi-screens of the past will still be present in cinema.

Considering cinema’s boundless direction, Kroitor’s and Ferguson’s interviews through the years generally included the question: What’s the future of cinema? In 2001, Roman Kroitor expressed his thoughts on multiple storytelling:

“When compared to literature, which can be evocative or poetic, etc, the concreteness of a single image is a barrier. When you put two images side by side – the right images side by side – then you can be 100 times more subtle, more wide ranging, more evocative or poetic. Technically it would be difficult and would have to be well thought–out beforehand. You would have to shoot it so it all came together properly. I think if you could do that, you could move cinema to another level. I think one day it will. Maybe not for many years, but someday it will happen” (Wise 33).

In 1997, Graeme Ferguson discusses if an eventual change from forty-minute documentary, travelogue films to ninety minutes is imminent:

“The term “feature” has got to be put in quotation marks because what has happened, although we have done two 90–minute films, in fact, our theatres mostly want 40 minutes. Originally this came from planetarium screenings that turn around on a quicker cycle. IMAX theatre can be run all morning, afternoon and evening. And they love that business of turning family audiences around in 40 minutes, and instead of seeing one 90–minute film, they will stay to see two 40–minute films. This will change, but right now in our industry those 40–minute films are widely shown and we call them features” (Wise 23).

In retrospect, Kroitor’s and Ferguson’s prediction of the future have already been fulfilled with the collaboration of Hollywood blockbusters and IMAX technology in films such as Avatar (Cameron, 2009) and The Dark Knight (Nolan, 2008). As Ferguson suggested, these films are well over ninety-minutes compared to the limited forty-minute documentaries. Furthermore, they allude to Kroitor’s vision of multiple storytelling. The feature-length films utilize different images and scenes simultaneously to depict a narrative. Avatar and The Dark Knight are among the many achievements in IMAX’s history. This would not be possible without Graeme Ferguson’s Polar Life and Roman Kroitor’s Labyrinthe at Expo 67 – the first event found on IMAX’s historic timeline.

The public is still experiencing IMAX developments in 2014. As mentioned, selected Hollywood blockbusters are using IMAX technology to film and project, like the most recent, Interstellar. While IMAX Hollywood blockbusters focus on its visual immersion, they realize an experiential experience and touristic gaze similar to Polar Life and Labyrinthe at Expo 67, the birthplace of IMAX. The theory developed by Andre Jansson of the touristic and future gaze at the Expo influenced the world fair’s creative and inventive nature on pavilions, transportation, and film. Although sensory immersion is a common theme in history, as Alison Griffiths examines, its technology will constantly change, as Kroitor’s and Ferguson’s IMAX continues to transform. Griffiths essay is also significant because she places an importance on observing the past to understand the present, similar to my examination of Expo 67’s influence on IMAX. The interview method made this study possible. It offered a personal yet informative perspective as all participants, from filmmakers to audiences, were instrumental at Expo 67. Engaging with a personal perspective, part of this process included a viewing of the digital re-creation of Polar Life at the Cinemateque Quebecois. It is a project organized by Monika Kin Gagnon, professor of the Expo 67 class mentioned at the beginning of my article. Montreal citizens will be opened to learn about their hometown’s involvement in IMAX and feel proud of it as I am. Having experienced both IMAX and its predecessor, I can fully acknowledge and appreciate the technology’s past and present while anxiously anticipating its future.

Bibliography

A Place to Stand. Dir. Christopher Chapman. 1967.

Avatar. Dir. James Cameron. 20th Century Fox. 2009.

BMZ Staff. “Interview With Under The Sea 3D Producer Toni Myers”. Big Movie Zone (February 13, 2009), 1-4.

D’Onofrio, Alberto. Interview with Antonello D’Onofrio. Conducted November 11, 2014.

ExpoVoyages. “Expo67.” Library and Archives of Canada. 3-CU-2 August 15, 1966. Web. 23 Nov. 2014.

Griffiths, Alison, “Expanded Vision, IMAX Style: Travelling as far as the eye can see,” in Shivers down your Spine: Cinema, Museums and the Immersive View (New York: Columbia UP, 2008), 78–113.

Interstellar. Dir. Christopher Nolan. Paramount Pictures and Warner Bros. Pictures. 2014.

In the Labyrinthe. Dir. Roman Kroitor, Colin Low and Hugh O’Connor. National Film Board of Canada. 1967.

Jannson, André, “Encapsulations: The Production of a Future Gaze at Montreal’s Expo 67.” Space and Culture 10, no. 4 (2007): 418–36.

Journal of the STMPTE. “Table 1: Presentations at Expo 67,” Journal of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers vol. 77 no. 3 (March 1968): 195.

Lamont, Austin F.. “Films at Expo: A Restrospective”. Journal of the University Film Association. Vol. 21, No. 1 (1969), pp. 3-12

McNamara, Carter, PhD. “General Guidelines for Conducting Interviews”, Minnesota, 1999

Napoleon. Dir. Abel Gance. MGM. 1927.

Polar Life. Dir. Graeme Ferguson. 1967.

Reuband, Karl-Heinz. “Oral History: Notes on an Emerging Field in Historical Research.”. Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung, No. 12 (October 1979), pp. 18-20

Siskind, Jacob, Expo 67 Films (Montreal: Tundra Books 1967). 2-40.

The Dark Knight. Dir. Christopher Nolan. Warner Bros. Pictures. 2008.

The Love Goddesses. Saul J. Turell. Paramount Pictures. 1966.

The Wonder of Photography. 1967.

Universe. Dir. Roman Kroitor and Colin Low. National Film Board of Canada. 1960.

Wise, Wyndham. “IMAX at 30: An Interview with Graeme Ferguson,” Take One no. 17 (Fall 1997).

Wise, Wyndham. Roman Kroitor: Master Filmmaker and Technical Wizard – Take One’s Interview. Take One no. 32 (May 2001).

Wise, Wyndham and Glassman, Marc. Take One’s Interview with Colin Low Part II. Take One (Winter 2000).

Zayas, Daniel. “Science Center Hosts IMAX Co-inventor.” Downtown Devil. Web. 23 Nov. 2014.

A Cinema of Loneliness

– – –

This is an essay that reviews and discusses Robert Kolker’s book on cinema: A Cinema of Loneliness.

Author: Alberto D’Onofrio

– – –

A Cinema of Loneliness is a book written by Robert Kolker, a professor of Film Studies and Digital Media. Along with A Cinema of Loneliness, he has written Film, Form and Culture, The Altering Eye (a book on European Cinema) and an online article, The Moving Image Reclaimed. While he has taught at three different schools in his career (University of Maryland, University of Virginia and Georgia Institute of Technology), his goal in teaching film has been the same: “Getting control of the image and handing that control over to students” (McGraw-Hill, 1). Kolker continues this statement by explaining that an audience cannot pause a film while it is playing at a cinema but with the technology of VCR and DVD, it is possible to become intimate with a film to allow a deeper analysis of it. This is an idea discussed by Kolker in the introduction to his book, A Cinema of Loneliness.

Kolker begins with an introduction that discusses the decline of assembly-line film production in the late 1950s and early 1960s – a system where major studios would have their own resources of producers, directors, writers and actors to quickly and efficiently make films. Television was a factor during this decline, which forced studios to experiment with Cinerama, Cinemascope, 3D and epics. While this time period included important films such as Vertigo (1958) and Touch of Evil (1958), it had economic issues by producing big budget films with no profit. This prompted studios to take low-cost risks on young filmmakers who, influenced by art cinema, delivered critical and challenging films. Kolker’s brief history of the studio system up to this point conveniently introduces the content of his book: an analysis of film directors who emerged and survived from this transitional state of the studio system. The directors in discussion are mainly Arthur Penn, Oliver Stone, Stanley Kubrick, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Robert Altman and David Fincher. While Fincher did not emerge from the same time period as the directors listed, Kolker introduces him in the book’s recent edition as another filmmaker who develops expressive and complex narratives. The author closes his introduction by writing that the technology allows him to view and analyze films like a book – having control of when to stop, look, or go back, which prepares the audience for a critical and deep analysis of cinema.

To briefly summarize the content of A Cinema of Loneliness, Kolker’s analysis of the directors is organized into five chapters: One: Penn, Stone, Fincher; two: Kubrick; three: Scorsese; four: Spielberg, and five: Altman. The author explains their styles by examining selected films and connects them with the subject of loneliness in films and our culture. Kolker describes a film noir-influenced Arthur Penn as having characters that are paranoid, trapped, and vulnerable as in Mickey One (1965) and Bonnie and Clyde (1967). The author attributes similar qualities to Oliver Stone and David Fincher in the same chapter. Stanley Kubrick is discussed as a filmmaker who is disconnected from commercial American cinema, which is why he was able to develop such complex narrative and cinematic space with his camera-work as Orson Welles did. His characters also deal with isolation, especially in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Kolker relates Martin Scorsese to Arthur Penn as having psychologically driven character studies such as Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver (1976), another connection to the term in discussion of loneliness. The author describes Steven Spielberg’s films as “absorptive and distributive” (Kolker, 325) meaning that he forces the spectator into his worlds and satisfies the audience, a world that is often built with special effects, a topic he also discusses alongside Spielberg’s films. While his characters can experience isolation, the author also suggests the isolation of the viewer within the realm of cinema. Finally, Kolker concludes with Robert Altman, a filmmaker who provides loose narratives with wide perspectives, demanding the audience to pay close attention, much like Douglas Sirk’s trust on the viewer’s imagination.

Kolker’s book is well structured. He begins with a historical introduction to lead into the start of the filmmakers’ careers and each chapter is dedicated to a certain approach to film and the directors’ styles. While they have stylistic differences, Kolker finds ways to connect them and he does so by exploring communication theories of ideology by Louis Althusser and encoding/decoding by Stuart Hall. A Cinema of Loneliness introduces these theories because they are important to how Kolker will examine his films without solely looking at form. Ideologically, films are embedded with social needs of a certain culture or group of people. These ideas are coded by the filmmaker and are open to be decoded by the audience. Along with communication theory, film theory is also discussed when explaining films in order to discuss their influences. For instance, Kolker writes about film noir and German expressionism when explaining Arthur Penn’s films and Sergei Eisenstein when discussing Oliver Stone’s way of cutting film. Expanding on film history, he discusses many films outside a director’s work. For example, he explains how Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990) emerges from Raoul Walsh’s The Roaring Twenties (1939).

From the explanation of Kolker’s writing approach to A Cinema of Loneliness, it is evident that there is a lot of information in this book, making it a dense reading. I believe it is because the author analyzes most of the major films of seven directors along with film theory, film history, and concepts of ideology. Taking an enormous amount of information and condensing it makes the book a challenge to follow. It was challenging to follow because the directors have different approaches to film and it is difficult to read a heavy analysis on Kubrick, move on to Scorsese, and then to Spielberg – three different directors who each deserve their own book. Albeit the challenging read, I appreciated Kolker’s attempt to connect each director’s work through the idea of loneliness. The connection is valid with the filmmakers having had a portrayal of these paranoid, self-centered characters in their work.

I enjoyed the addition of David Fincher in the author’s fourth edition of the book. Being one of my favorite directors, it was interesting to read an academic analysis on The Social Network (2010) for the first time. A minor aspect I found disappointing was the inclusion of Oliver Stone’s Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (2010) and the disregard of The Doors (1991). Although the film did not have a true rendering of Jim Morrison, I found it more interesting than the Wall Street (1987) sequel, especially in the way it was edited (this could have been an interesting analysis with Eisenstein in discussion).

Martin Scorsese is the only filmmaker with a reported one-line review of the book that states A Cinema of Loneliness, “Brings the films into clearer focus for film-goers. The filmmakers themselves will find Kolker’s analysis of their works extremely accurate” (Oxford University Press, 1). While the information is dense, Kolker demonstrates a great understanding of film history, theory, and the movies in discussion.

Bibliography

2001: A Space Odyssey. Dir. Stanley Kubrick. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. 1968. Online.

“A Cinema of Loneliness”. Oxford University Press. 2011. Web

http://global.oup.com/academic/product/a-cinema-of-loneliness

Bonnie and Clyde. Dir. Arthur Penn. Warner Bros. 1967. Online.

The Doors. Dir. Oliver Stone. TriStar Pictures. 1991. Online.

Goodfellas. Dir. Martin Scorsese. Warner Bros. 1990. Online.

Kolker, Robert Phillip. A Cinema of Loneliness. New York: Oxford UP, 2011. Print.

McGraw-Hill Companies. “Robert Phillip Kolker: About the Author”. 2001. Web.

http://www.mhhe.com/socscience/art-film/kolker2/author.html

Mickey One. Dir. Arthur Penn. Columbia Pictures. 1965. Online.

The Roaring Twenties. Dir. Raoul Walsh. Warner Bros. 1939. Online.

The Social Network. Dir. David Fincher. Columbia Pictures. 2010. Online.

Taxi Driver. Dir. Martin Scorsese. Columbia Pictures. 1976. Online.

Touch of Evil. Dir. Orson Welles. Universal Pictures. 1958. Online.

Vertigo. Dir. Alfred Hitchcock. Paramount Pictures. 1958. Online.

Wall Street. Dir. Oliver Stone. 20th Century Fox. 1987. Online.

Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps. Dir. Oliver Stone. 20th Century Fox. 2010. Online.

Post-Modernity and Human Rights Activists in Latin American Cinema

– – –

My last of three essays on Latin American Cinema. I analyze the films Maquilapolis and When the Mountains Tremble in relation to post-modernity and human rights activists in Latin American Cinema.

Author: Alberto D’Onofrio

– – –

“You can say a story is fabricated. You can say a jury is corrupt. You can say a person is lying. You can say you don’t trust newspapers. But you can’t say what you just saw never happened” (Speakers, 1). This is the message written in WITNESS’s promotional video, an organization co-founded by Genesis musician Peter Gabriel that encourages worldwide human rights activists to make changes through the use of video. This objective reflects Gabriel’s message that an event should be captured by an activist to expose injustice and reveal the truth. Relating to the general topic of Latin American Cinema, three filmmakers will be discussed in relation to Peter Gabriel’s solution for truth: Vicki Funari, Sergio De La Torre, directors of the 2006 film Maquilapolis and Pamela Yates, director of the 1984 film When the Mountains Tremble. The main difference between the directors of each film is that Yates, unlike Funari and De La Torre, Yates, is a New York citizen and an outsider from Latin America, but they nonetheless share the same concern for each film’s subject matter. When the Mountains Tremble documents the horrific genocide of the Mayan civilians by the Guatemalan army while Maquilapolis documents the lives of maquiladora workers who are experiencing the weakening effects of the toxic industrial waste of the factories.

Both films challenge social justice while also being part of the post-modern era of documentary filmmaking. As theorist Linda Williams describes it, post-modern documentaries share the earnest approach to a subject as always but the truth is constructed by docu-auteurs who whether on or off camera have control of the shots (Williams, 104) and as writer Gloria Galindo expands on Williams’ theory, this style borrows features from fiction film in their construction (Galindo, 83). Integrating Peter Gabriel’s message of truth with Linda William’s theory of post-modernity, Maquilapolis and When the Mountains Tremble are films that represent truth by being made in collaboration with human rights activists while the filmmakers construct the film with a post-modern approach by blurring the lines of documentary and fiction. To write chronologically, I will begin the development of my thesis with When the Mountains Tremble.

Theorist Teresa Longo expresses the same concern I explained earlier: When the Mountains Tremble was a United States filmmaker making a film about a Third World Country. Despite the U.S. involvement, Yates was intrigued in telling a story of what she describes as a “hidden war” and led to the director making a film that was more “transcultural than ethnocentric and objectifying” (Longo, 77), meaning the director documented the genocide by the Guatemalan army through the eyes of the Maya people and not with a U.S. perspective. This was made possible by collaborating with human rights activist Rigoberta Menchu who served as a storyteller with an indigenous (meaning original and truthful) voice (Skylight Pictures, 15). Menchu’s importance in the film is evident in its opening sequence as she delivers the first dialogue. Wearing a distinct blue ensemble, Menchu stands out strong from the black background and introduces herself as part of the Maya people, giving authority to the film. This collaboration also has an important relationship to the visual imagery selected by the director and even more so to the re-enacted scenes, an aspect of the blurred lines of documentary and fiction.

Menchu introduces the re-enacted scenes based on declassified U.S. documents by stating, “However, some years ago there was hope for a democracy”. Both re-enacted scenes of the dinner with Guatemalan President and the CIA command post were juxtaposed with monologues by Menchu and at one point, her voice acts as voice-over to the reenacted sequence. This is one of the examples given by Teresa Longo that made the film transcultural as it joined images of Menchu and the fiction-based conventions of the director to explore the U.S. history in relation to the events in the Third World Country (Longo, 79). The collaboration with activists and post-modern filmmaking demonstrated in When the Mountain Trembles has been explored twenty-two years later in Maquilapolis.

While taking a course on Latin American Cinema, professor Elizabeth Miller sparked an interesting discussion on Maquilapolis, which was that we (the class) has previously discussed the aesthetics of hunger in relation to the Cinema Novo Movement, but now with Maquilapolis, how would we describe its aesthetics of access? This was interesting as it reflects the collaboration between Vicki Funari, Sergio De La Torre and the maquiladora workers. The directors wanted to work with women who are activists and they taught the woman factory workers how to use a digital camera, film techniques, sound recording, and writing skills in order to tell their story (Fregoso, 3). This collaboration offered a personal insight to the women’s lifestyles while granting extraordinary access to the factories they have suffered in and the unprivileged homes they live in with their family. The access seen in the film at the factory justifies the gritty and toxic surroundings the woman are standing up against while the access in their homes and lifestyle justifies their strong-willed characteristics, making the audience realize that they deserve better. The collaboration offers subjective truth, an aspect of post-modern documentary, a mode that also includes fictional elements.

Along with this collaboration, the filmmakers combine the documentary realism with choreographed performances of the maquiladora workers that acts as the film’s fictional elements. The workers, dressed in blue, demonstrate a repeated movement of their hands that resemble the work they do in the factory. The docu-auteurs add a personal touch to the film by juxtaposing beautiful imagery of the dance with the dark undertones of the factory. Now free from work at the factory, the film concludes with the workers slowly spreading apart from line and walking free as the camera moves further to a Bird’s-eye Point-of-View shot. Sounds like a scene in a Hollywood movie. Like Linda William’s explains, post-modern documentary take part in “a new hunger for reality on the part of the audience apparently saturated with Hollywood fiction” (Galindo, 83). As director Funari explains, it is the combination and the dynamics you get of the performance and the standard verite elements that makes the project interesting while expressing the films themes, characters, and place (Fregoso, 176) – a true representation of facts in a post-modern approach.

To synthesize both films as a part of post-modern cinema, both films show a constructed truth by the directors with the help of human rights activists. Peter Gabriel’s WITNESS promotional video concludes by demanding to give cameras to the world to start shooting and revealing the injustices of the world (Speakers, 1), which is what Maquilapolis and When the Mountains Tremble does effectively in collaboration with human rights activists. As Gabriel optimistically explains, this approach to a self-reflexive style of documentary is expanding especially with the technological developments of portable camera-phones where practically any human rights activist can be a docu-auteur and reveal the truth.

Bibliography

Galindo, Gloria. Bus 174 and Post-Modern Documentary. Theoria, Vol. 18 (1): 81-86, 2009.

Fregoso, Rosa-Linda. “Maquilapolis: An Interview with Vicky Funari and Sergio de la Torre”. Camera Obscura 74, Vol 25, Number 2, Duke University Press, 2010.

Longo, Teresa. “When the Mountains Tremble: Images of Ethnicity in a Transcultural Context” Framing Latin American Cinema, University of Minnesota Press, 1997, p. 189-206.

Maquilapolis. Dir. Vicki Funari and Sergio De La Torre. California Newsreel. 2006. Film.

Skylight Pictures. Granito Press Release. Press Release. 2013.

“Speakers Peter Gabriel: Musician, Activist.” Peter Gabriel. N.p., n.d. Web. 16 Nov. 2013.

When the Mountain Trembles. Dir. Pamela Yates. Skylight Pictures. 1983. Film.

Williams, Linda. “Mirrors Without Memories: Truth, History and the New Documentary” New Challenges for the Documentary Ed: Alan Rosenthal and John Corner. New York: Manchester University Press, 2005.

Bus 174 and City of God

– – –

My second of three essays on Latin American Cinema. I analyze the films Bus 174 and City of God.

Author: Alberto D’Onofrio

– – –

Sandro Rosa do Nascimento, a young man in his twenties, holds a hostage in his arms with a gun at her head inside Bus 174 of Jardim Botanico, Rio de Jeneiro, Brazil. The man yells at the camera, “This is not an action movie, this is a serious matter!”. One without a hint or clue of this scene description might possibly convey it as well-written dialogue in a self-reflexive fiction, meaning, “consciousness turning back on itself” or films which call attention to themselves as cinematic constructs (Siska, 285). Unfortunately this is not the case. Albeit its self-reflexivity, the 2002 film Bus 174 directed by Jose Padilha documents the event of young protagonist Sandro who holds a bus hostage for four hours. The camera he addresses is part of a flock of cameras covering the event live for television and there is no one to yell cut to his actions. The event and consequences are real, which overall depicts the violence of Brazil’s society.

The year 2002 was a witness to another great Brazilian film City of God directed by Fernando Meireilles, a film about the growth of a crime gang in the suburbs of Rio de Janeiro. Now why would the fiction film City of God be mentioned in the same breathe as the documentary film Bus 174? Ask the critiques of Bus 174. To select a few, Jamie Russel of BBC states, “A stunning indictment of Brazil’s social meltdown, this startling documentary plays like City Of God – except this time the bullets are real” and Empire summarizes that, “If City Of God cracked the skin, Bus 174 digs deep into the wound”. These are brief comments about the films similarities but they are accepted in a movie review. As Timothy Corrigan explains, movie reviews are an introduction of the film to the general public, but he also explains the critical essay, a deeper evaluation that focuses on the film’s themes and any other filmic observations (Corrigan, 7-10). That is my job here. Collecting opinions of theoretical author’s and my own, I will analyze what makes City of God similar to Bus 174. In terms of form, while one is a documentary and another a fiction, they each contain a small but significant element of their opposite form to blur the lines of documentary and fiction. Thematically, both films depict the aspect of violence in Brazil’s society. Combining form and theme, Bus 174 and City of God realistically portrays the social issues in Brazil that ultimately categorizes both films under the Cinema Novo movement of Latin America, a movement that captured the underdevelopment of Latin America.

Else R. P. Vieira, Professor of Latin American Studies, states that City of God utilizes hegemonic models and mainstream film language (Vieira, 51). The open sequence of the fiction film is a representation of this. It begins with fast-paced, extreme close-ups of knives, the celebratory Brazilian community killing chickens followed with another stylized sequence of a chase with guns for a fleeing chicken. The sequence ends with our hero, Rocket, a young man with a camera, who stands close to the chicken while confronted by a gang on one end and the police on the other. While contemplating whether he should take a picture of the event, he narrates, “A picture could change my life, in the City of God, if you run away, they get you and if you stay, they get you too. It’s been that way ever since I was a kid”.

Comprising mostly of fictional elements, there is still subtle documentary traits that incorporates filmmaker and anthropologist Jean Rouch’s ethnofiction genre, a subgenre of docufiction that means, “any fictional creation with an ethnographical background” (Ross, 1) by using actors and scripts. The film utilizes the docufiction technique by using real people from the favela as actors. Expanding on this, Vieira explains that two hundred children and adolescents were trained during preproduction allowed great spontaneity in the film, which would need a handheld camera to capture it. Real people and handheld cameras are usual motifs to the documentary genre to capture the truth and reality of a given topic or event – this being violence in Brazil that was also depicted in Bus 174.

Author Gloria Galino categorizes Bus 174 under post-modern documentary because it borrows features from fiction film. This is evident in the opening frames of the film as it begins with a near four-minute long shot of Jardim Botanico as it gets close to the scene of Sandro’s crime accompanied with a string-orchestrated soundtrack. Gloria Galino is inspired with theorist Linda Williams’ who states, “post-modern documentaries take part in a new hunger for reality on the part of the audience apparently saturated with Hollywood fiction, but with a sense that truth is subject of manipulation and construction by docu-auteurs who, whether on camera or behind it, are forcefully calling the shots” (Galino 83). Director Jose Padilha has power to make the film how he wishes which develops into a documentary that displays the intensity of a fiction. This also relates to self-reflexivity, which as mentioned previously, addresses the construction of a film where the voice of the director is evident.

In my opinion, the most effective choice made by the director was to break time and space by juxtaposing footage of the live event with parts of the film that reflect on Sandro’s traumatic past of his mother being murdered by interviewing people who know him. Linda Williams calls this aspect of the film, “mirror with memory” (Galino, 84). Since they are exploring the past, this cannot be captured, therefore it needs to be constructed through memory and as French philosopher Jacques Ranciere defines it, memory is a “work of fiction”. It is subjectively constructed from an individual while viewing objective accounts (Ranciere, 158). Theorist Belinda Smaill expands on the director’s decision to not organize the film to offer a single, one-sided reading which makes the documentary provoke drama and suspense because of the analysis of the protagonist’s psyche (Smaill, 185). I mentioned Else R. P. Vieira’s statement earlier that City of God utilizes hegemonic models and mainstream film language. Bus 174 follows that statement and she continues that both qualities are necessary to achieve success internationally. Bus 174 is the first Latin American documentary that was show in cinemas and film festivals around the world. Along with City of God, it was an international success.

To synthesize both films as a part of Latin American Cinema, City of God and Bus 174 represent Cinema Novo, a movement that represents Latin’s “cultural manifestation” of violence (Vieira, 54). Inspired by Italian Neo-Realism, both of the documentary and fiction films utilize real people to demonstrate the truth of violence in Brazil whether it is on an animal, an inanimate object such a soccer ball or on each other. This movement, and the effectiveness on documentary and fiction film is proving to be inspiring young Brazilian filmmakers such as Maria Clara Escobar. Having the opportunity to view her film, Os Dias Com Ele (2013) at the Montreal Festival Du Nouveau Cinema, I can see the influence of Cinema Novo as she uses memory to blur the lines of fiction and documentary to reflect on Brazil dictatorship of the 1960’s and 1970’s. I predict the value of constructing documentaries and fiction with this approach will only grow.

Bibliography

Bus 174. Dir. Jose Padilha. Zazen Producoes. 2002. Film.

“Bus 174Documentary about the Kidnapping of a Bus Full of People in Brazil.” Empireonline.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 Oct. 2013.

City of God. Dir. Fernando Meirelles. Miramax Films. 2002. Film.

Corrigan, Timothy. A Short Guide to Writing about Film. Second Edition. New York: Harper Collins, 1992, 6-15.

Os Dia Com Ele. Dir. Maria Clara Escobar. 2013. Film.

Rancière, Jacques. The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. London: Continuum, 2006. Print.

Reuben, Ross. “Ethnofiction and the Work of Jean Rouch | UK Visual Anthropology.” UK Visual Anthropology. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 Oct. 2013.

Russell, Jamie. BBC News. BBC, n.d. Web. 28 Oct. 2013.

Siska, William C. “Metacinema: A Modern Necessity.” Literature/Film Quarterly, 7.1 (1979): 285-9.

Smaill, Belinda. The Documentary – Politics, Emotion, Culture, 2010, p 182-188

Vieira, Else R. P., Cidade de Deus: Challenges to Hollywood, Steps to The Constant Gardener In Contemporary Latin American Cinema (pp 51-66).

Guzman: Intersecting Fiction and Documentary

– – –

My first of three essays on Latin American Cinema. I analyze the films of Patricio Guzman: The Battle of Chile and Obstinate Memory.

Author: Alberto D’Onofrio

– – –

Ignacio, an eighty-year-old man, sits at his piano and performs a melancholic composition that appropriately acts as a diagetic soundtrack to the film Obstinate Memory, a 1997 film directed by Patricio Guzman. The filmmaker asks the man, “What does remembering mean to you?” and he replies, “Remembering is returning to the past… you see the past as it was”. Ignacio refers to the events chronicled in Guzman’s three-part documentary The Battle of Chile. Returning to the past is not only significant to Obstinate Memory but also a reference to Latin American Cinema as its origin reigns from the critical realist style of filmmaker Fernando Birri (King, 417), a style that is present in Obstinate Memory and Battle of Chile (Guzman, 1975-1978). True to John King’s explanation of Latin-American Cinema, the films have a desire to, “Explore a fractured past and imagine different futures” (King, 417) while The Battle of Chile’s cinematic sensibility and Obstinate Memory’s subjectivity challenges truth and representation as Guzman intersects fiction and documentary.

Guzman’s film, The Battle of Chile, is a documentary that incorporates fictional and cinematic sensibilities that heighten the critical-realist style of Latin American Cinema, a style that, as John King describes it, represents and encourages social change (King, 399). The political background of the film begins with the bombing of the presidential palace. This marked the end of Popular Unity, the democratically socialist government under Salvador Allended, and initiated a dictatorship (Klubock, 272). The event provoked the citizens of Chile to protest, which was effectively captured by Guzman and his crew.

The documentary aspect of the film is evident. It utilizes a cinema-verite style that was developed in the 1960’s after the innovations of transportable cameras and synchronous sound, technologies that allow a true representation of reality (Glossary, 1). The film demonstrates the ability of the handheld camera for flexible coverage as it captures the events up-close and personal. Sound technology is also visible to the viewer as the sound operator strikes the microphone to allow post-production syncing. Although this would be cut in most films, cinema verite encourages the filmmaking process and this only heightens the reality of the moments captured.

The advantages of transportable technology to capture live events are not only evident in the film, but also the history of its production, which is detailed in The Battle of Chile’s Press Release. Guzman explains that, “You would be sitting in a café, working on a script, and all of a sudden a group of picketing workers with red flags would pass by… How could you not film that? Why distance oneself from that reality?” (Icarus Films, 13). The small anecdote validates the reality of the film. It explains the ability to capture events that have no schedule – they can happen anywhere, anytime. Although the film is labeled as a documentary, Guzman wanted to avoid the typical, informative style of this category.

As a filmmaker who studied fiction film (Icarus Film, 14), Guzman’s The Battle of Chile offers a cinematic and fictional representation of true events. The film includes cinematic coverage of the interviews, where the focus is not solely on one person and their opinions, but also the emotions they convey. This is executed through extreme close-ups and unusual camera angles. For example, an interview includes an upset but passionate woman who is covered in extreme close-ups, a type of shot that compliments her emotions. Another interview includes a woman expressing her views with pride and confidence, hence a low-angle camera angle is used. This evokes the power and strength of the woman’s message and personality while also covering the crowd that stands strong and proudly with her. As authors Victor Wallace and John D. Barlow examine Guzman’s cinematic sensibility, it is a “Hollywood portrayal of the forces of liberty opposing those of tyranny” (Wallace and Barlow, 410). “Hollywood portrayal” is an interesting choice of words for Wallace and Barlow as it explains the fictional elements of Guzman’s coverage of the Chilean citizens. Observing reality with fictional terms, the film’s main actors are real, working class Chileans, who serve as clear protagonists to the military coup, the antagonist.

Guzman’s intention with The Battle of Chile was to make an analytical documentary that can be observed and studied by Chileans in the future (Icarus Film, 14), which supports John King’s explanation of the critical-realist style of Latin American Cinema that suggests social change. I believe that because Guzman captured the events in such a cinematic way, the power of the film is heightened which allows an effective and emotional analysis for future Chileans. Guzman’s intention became a reality when his 1997 film Obstinate Memory was released.

Guzman screened The Battle of Chile to his Chilean community for the first time after being band for decades by the authorities (IMDb). Separating The Battle of Chile from Obstinate Memory, Thomas Kublock describes the 1970’s three-part film as, “Cinema verite. It was an unrepeatable social experience. The second [Obstinate Memory] is a more personal film about remembering” (Kublock 125). In Obstinate Memory, new generations of Chilean citizens reflect then events they barely remember along with those who lived it. Consistent with the ideology developed in The Battle of Chile of combining documentary and fiction, Guzman utilizes “memory” as subjectivist fiction (Rodriguez, 47) in Obstinate Memory.

As French philosopher Jacques Ranciere defines it, memory is a “work of fiction” Memory is subjectively constructed from an individual while viewing objective accounts (Ranciere, 158). Relating Ranciere’s theory to the film, Obstinate Memory includes youths and elders watching The Battle of Chile (objective), and later includes their reactions and reflections (subjective). Guzman uses the film as a way to access memory and does effectively as it sparks an inspired debate amongst university students, and emotional reflections from those who experience the terrors of that period. According to Ranciere, “Cinema is the art best equipped to represent the operations of memory because it is the combination of the gaze of the artist who decides and the mechanical gaze that records, of constructed images and chance images” (Ranciere, 161). The film reflects this quote as segments of the film show archival footage from The Battle of Chile that are cinematically edited by juxtaposing images of the citizens between now and then, while also creating spaces where citizens watch the three-part film in groups or individually.

Memory as fiction in Obstinate Memory does challenge the notion of truth and representation. Thomas Kublock explains that critics believe oral testimonies do not allow a true understanding of past experiences because memories can be mistaken and distorted (Kublock 275). For example, Ignacio struggles to remember and conveys this in a comical manner as he tries to play the soundtrack to the film “Beethoven’s Sonata”. Guzman introduces his uncle Ignacio and narrates, “He still has good memory. I think”. Guzman is not sure of his uncle’s ability to remember, therefore labeling his memory as subjectivist fiction. Although subjective memory challenges truth and representation, the film is definitely true to John King’s idea of Latin American Cinema. Obstinate Memory “explore[s] a fractured past and imagine[s] different futures” (King, 417). This film succeeds as it initiates discussions between students of what is right and wrong in order to build a better society.

The Battle of Chile and Obstinate Memory is an ideal combination of critical-realist films from Patricio Guzman as both incorporate fictional elements in the documentary category. Interestingly, recent Latin American Cinema has witnessed a reversal of this idea as documentary elements are incorporated in the fiction category. No, a 2012 film directed by Pablo Larrain, is based on true events of an advertising executive that creates plans to promote the NO campaign to oppose a plebiscite on the Chilean dictator. For authenticity, Larrain did various things: to recreate the look of the period, the film was shot on a 1983 U-matic video camera in a 4:3 ratio, he used many TV spots from 24 years ago that were seamlessly accompanied with new footage, and similar to The Battle of Chile, it was shot hand-help for spontaneous coverage (Sony Pictures Classics, 10). As Pablo Larrain’s brother and producer No expresses in the film’s Press Release, “Pablo wants the camera to be as much a participant in scenes as the actors. [He] likes his camera to get dirty” (Sony Pictures Classics, 9).

The Chilean filmmakers Pablo Larrain and Patricio Guzman seem to have adopted the style of filmmaking that Fernando Birri has established for Latin American Cinema. Although The Battle of Chile, Obstinate Memory and No are in different film categories, they are example of critical realist films with great cinematic value that reflect social change and truth. When films offer critical and truthful insight of the past, they will always remain significant. Whether documentary with fictional elements or vice-versa, it serves as a document of the past. Audiences can learn from cinema and gain knowledge on how to shape society’s future.

“Chile, the Obstinate Memory.” IMDb. IMDb.com, n.d. Web. 23 Sept. 2013.

“Glossary of Rouchian Terms.” Glossary of Rouchian Terms. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 Sept. 2013.

Icarus Films. “The Battle of Chile Press Release”. Press Release. 1998.

King, John. “Chilean Cinema in Revolution and Exile” in New Latin American Cinema: Volume Two: Studies of National Cinemas Ed. Michael T. Martin. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1997. 397-419.

Kublock, Thomas. “History and Memory in Neoliberal Chile: Patricio Guzman’s Obstinate Memory and the Battle of Chile” Radical History Review, Issue 85, winter, 2003. 272-281.

No. Dir. Pablo Lorrain. Sony Pictures Classics. 2012. Film.

Obstinate Memory. Dir. Patricio Guzman. Icarus Films. 1997. Film.

Rancière, Jacques. The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. London: Continuum, 2006. Print.

Rodriguez, Juan Carlos. “The Post-Dictatorial Documentaries of Patricio Guzman”. Duke University, 2007. Print.

Sony Pictures Classics. “No Press Release”. Press Release. 2012.

The Battle of Chile. Dir. Patricio Guzman. Icarus Films. 1975-1978. Film.

Wallace, Victor and Barlow, John D. “Documentary as Participation: The Battle of Chile” in Show Us Life: Towards a History and Aesthetics of the Committed Documentary NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1984, p. 403-416.

8 Mile: A Study of Hip-Hop Culture

– – –

This is an essay that analyzes the film 8 Mile and how it depicts and challenges the culture of Hip-Hop.

Author: Alberto D’Onofrio

(sorry in advance for some inconsistency in the essay’s formatting in the lyric segements – WordPress is giving me some problems)

– – –

PREFACE

Music is not isolated to a vinyl pressing, compact disc, or audio file. It is a versatile art form – a statement I realized while studying media, in and out of school.

Cinema is a passion of mine to study, produce and enjoy. Most of all, it is a medium that can utilize music while also define a music genre. Music is another passion of mine and I am fortunate that both mediums are unifying art-forms. For instance, some of my most favored films are illustrations of a musical time period and define its depicted music genre. They also confront and demonstrate issues around the given culture. To name a few, Almost Famous: Rock and Roll in the 1970’s, Walk the Line: Johnny Cash and Country music, A Hard Day’s Night: The Beatles and the British Invasion and finally, the focus of my essay –

8 Mile: A Study of Hip-Hop Culture

Of the numerous films made about the four-decade long Hip-Hop culture, Curtis Hanson’s 2002 film 8 Mile featuring Eminem and his semi-autobiographical story is among the most successful. It frequently makes the list of “best hip-hop movies” (Ramirez, 1) and is an example of commercial success meeting artistic achievement. While the film grossed 240 million at the box office (Box Office Mojo), it was acclaimed by film critics and Eminem’s “Lose Yourself”, part of the 8 Mile’s thematic score, was rewarded an Academy Award for Best Original Song (the first Hip-Hop artist to do so). However, a “two-thumbs up” from famed critic Roger Ebert and a golden statue is not my criteria for artist achievement.

My film analysis will accompany the cultural theories of Hip-Hop by theorist Murray Forman in “The Hood Comes First: Race, Space and Place in Rap and Hip Hop” and Jeffery O.G Ogbar in “Hip Hop Revolution: The Culture and Politics of Rap”. Major elements of this analysis will include the role of the MC and Race, Space and Place in Hip-Hop culture which Forman discusses and is demonstrated by director Curtis Hanson in 8 Mile. The film is set during the backdrop of underground rap battles in Detroit where MC’s use words to “vividly depict contemporary life” (Forman, 95). The writing, locations and performances of the battles relate to the artist’s life and surroundings, or as Forman suggests, “space and place”.

Race is also part of the narrative. In the film, main character B-Rabbit (Eminem) struggles to make an impact as a Hip-Hop artist in the Black community of Detroit. This racial element is explored throughout the film, and especially summed in a discussion between B-Rabbit and his entourage of close friends: DJ IZ tells B-Rabbit, “There’s always room for a White man in a Black man’s world”.

My analysis of 8 Mile will be an example of why the film is an artistic achievement as it relates to the large culture of Hip-Hop as theorized by author Murray Forman and Jeffery O.G Ogbar. There are different approaches to writing about a film and I will use a critical essay methodology (Corrigan, 12). With this method in practice, I presume that the reader will be familiar with 8 Mile as I analyze its components, such as setting, character and language, in relation to Hip-Hop culture.

8 Mile is a semi-autobiographical account of Eminem, therefore a 1995 Detroit setting is appropriate. Eminem grew as a person and rapper in this time and place which is a reflection of B-Rabbit, the main character of the film. Setting is an important element in film language to help convey the theme, build an atmosphere and make the film believable. Detroit was a motivated setting to associate music and race as depicted in 8 Mile.

As represented in the film, the Hip-Hop culture in Detroit is one that depicts a division of race and social class. However, Detroit is not only an important city for Hip-Hop as author Chris Quispel titles the city with Detroit: City of Cars, City of Music. This is a title the author relates to the rise of Motown Records in the 1960’s and 1970, a time period that also reflects social and racial division with music as it did with Hip-Hop. Motown was one of the most important Black record labels in the United States and “Although almost everybody involved with the Motown label was Black, the music was successfully aimed at both a Black and White audience – this despite the volatile and hostile racial relations in Detroit” (Quispel, 226).

The hostile racial relations that Quispel examines is an issue that reached its climax in the summer of 1943 when the race riot occurred. Fights between young Blacks and Whites erupted and fought for several days. “34 people were killed, 25 of them Black, 675 were seriously injured and 1,893 people were arrested” (Quispel, 229) and this riot was a result of the growing competition between Blacks and Whites, a relationship that audiences witness in 8 Mile.

The depiction of Detroit’s racial and social relations in the film is already referenced in the title 8 Mile. The film’s title refers to 8 Mile Road in Detroit, a border in between 7 Mile Road, the Black neighborhood, and 9 Mile Road, the White neighborhood. Its division is physical and metaphorical as it separates two different cultures and communities (Esling, ch.8, location 1553). In the film, we see the difference between the White and Black neighborhood. When B-Rabbit and his entourage visit their friend Cheddar-Bob after his accident, they are in a White neighborhood. Director Curtis Hanson paces the scene in comparison to the neighborhood itself – slow, mundane and it lasts a striking two minutes compared to the rest of the film where it mostly takes place in a fast and eventful Black neighborhood with Hip-Hop clubs such as The Shelter, the streets and Detroit Stamping. The 8 Mile Road division in this instance can also be an indication between reality and aspiration. B-Rabbit, if unsuccessful in his career, may lead a mundane life but he aspires to become part of the Hip-Hop scene in 7 Mile Road and beyond.

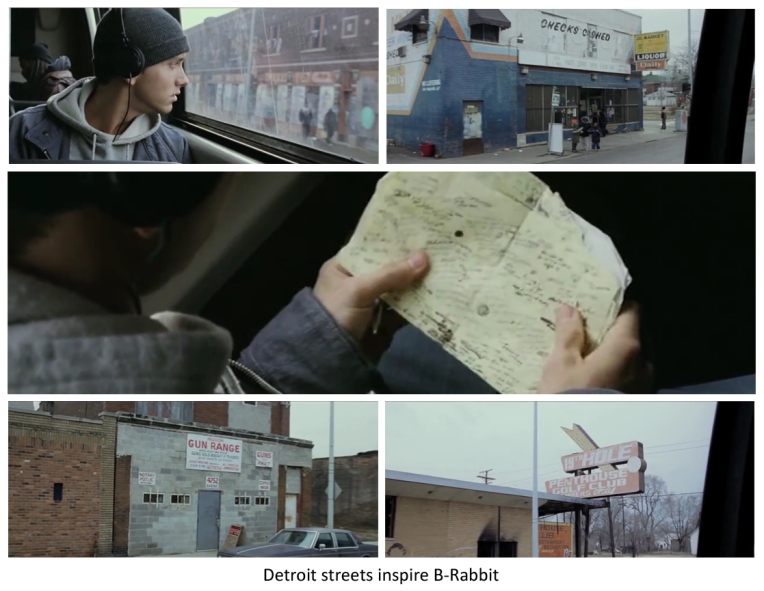

While B-Rabbit spends most of his days in the Black neighborhood, he finds inspiration in the streets, at his job in Detroit Stamping and The Shelter. He rides the “8 Mile” bus to work and gazes out the window as the gritty streets of Detroit pass by. The character looks over at a liquor store, a gun range and a golf club – they are run-down with low maintenance which displays the area’s poverty. B-Rabbit then writes lyrics on a sheet of paper (that is old and mostly filled, showing that he is inspired and writes frequently) over the beats on his walkman. As Nas used the scenes in Queensbridge to inspire the artist’s masterful Illmatic (XXL Staff), B-Rabbit uses the Detroit scene to inspire his writing. The lyrics written in this scene eventually become a song titled “8 Mile” by Eminem on the film’s soundtrack, named after B-Rabbit’s bus. Segments of these lyrics display the character’s frustration of living in Detroit:

I just can’t do it, my whole manhood’s

just been stripped, I have just been vicked

So I must then get off the bus then split

Man fuck this shit yo, I’m going the fuck home

World on my shoulders as I run back to this 8 Mile Road

Detroit crime is also an aspect of the film. At one point, it introduces a murder and rape crime towards a young girl. Eventually, B-Rabbit and his entourage burn down the house where it took place which serves as another inspiring event to the rapper’s lyrics. As he works at the Detroit Stamping factory (another setting of inspiration), he sings:

Alex Latourno, Hotter than an inferno

Hotter than a crack house

Burn internal

He combines events of the night before: the start of his love interest with Alex Latourno and the burning of a crime scene.

B-Rabbit writes from personal experience which is the reality of Hip-Hop artists like, as mentioned earlier, Nas and his album Illmatic. This idea relates to an important theoretical outlook on Hip-Hop from Murray Forman’s book on the importance of space and race in the Hip-Hop narrative. Spaces, such as the city or the ghetto, can influence the music and the stories being told through the lyrics (Forman, 88) as the streets of Detroit inspire B-Rabbit’s narrative lyrics. With the help of Communications theorist Michel de Certeau, Murray Forman expresses the use of narrative in Hip-Hop as it is an important cultural element that offers insight on space. In Hip-Hop, the MC uses words to “vividly depict contemporary life” (Forman, 95).

Director Curtis Hanson depicts settings in 8 Mile with such grit and realism that B-Rabbit’s inspiration with Detroit is motivated and justified. Cinematically, this is accomplished by shooting on location while capturing the film with handheld and dark-toned cinematography. It offers a distinct parallel with the characters that inhabit the locations. Not only do the settings reflect the characters, but it reflects Hip-Hop culture as well with its use of The Shelter, a Detroit Hip-Hop club. Again, the director uses a real location to heighten the film’s authenticity. The Shelter, as described by author Jordan Ferguson, was a venue for people to showcase their talent (Ferguson 18). The main attractions were the “open mic battles that took place on Saturdays between 5:00 and 7:00 p.m. The Saturday battles and the shop as a whole became a mandatory destination for Hip-Hop heads, a space wholly dedicated to the love and appreciation of the music and the culture, and a place for the city’s growing crew of artists to network and collaborate” (Ferguson 10). In relation to 8 Mile, the venue represents the struggles of a White man trying to become successful in a Black setting. The film’s sequences at The Shelter are examples of Curtis Hanson’s use of character and language in relation to Hip-Hop culture. I will examine B-Rabbit’s struggle in a racial setting from rap battle lyrics heard at the venue.

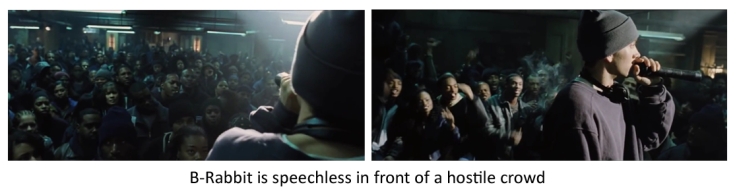

The Shelter is part of the first scene in the film as B-Rabbit prepares in the venue’s bathroom for a rap battle. The scene cuts to a battle on stage, showing a Black rapper vs another in front of a predominantly Black audience. Future, B-Rabbit’s friend and host of the rap battles, escorts B-Rabbit to the stage. He and his African-American opponent Lil’ Tic are ready to battle. Lil’ Tic starts first and what follows are important excerpts from his battle:

I’mma murder this man!

He’s the type to lose a fight with a dyke

They don’t laugh cause you’re whack, they laugh cause you’re white with a mic

You a wigger that invented rhymes for money

My paws love to maul an MC

Cause he’s faker than a psychic with caller ID

So that bullshit, save it for storage

Cause this is hip hop, you don’t belong you’re a tourist

So put ya hockey stick and baseball bat away

Cause this here Detroit, 16 Mile road thataway, thataway

Examining these lyrics, Lil’ Tic incorporates racial comments as he takes advantage of B-Rabbit’s isolation in their Black community. This is evident in the battle’s opening line, “They don’t laugh cause you’re whack, they laugh cause you’re white with a mic”. Shortly after, Lil’ Tic uses the term “wigger”. This is a slang term that is defined as a White person that tries to act Black. He accuses B-Rabbit of being a rapper with no passion that writes meaningless rhymes just to make money, which Lil’ Tic follows up and calls it “bullshit” material (Black Papillon, 1).

Hip-Hop is known as being an African-American genre. Hip-Hop theorist Jeffery O.G Ogbar supports this claim by acknowledging that Hip-Hop was born from the expressive culture of the African-American’s. For example, Ogbar explains that the core of Hip-Hop was influenced by African-American pop culture such as James Brown and his dance moves influencing breaking dancing (Ogbar 12). Therefore, as Imani Perry is quoted by Ogbar, “Hip-Hop music is black American music” (Ogbar 12). This is why Lil’ Tic refers to B-Rabbit as a tourist – “Cause this is hip hop, you don’t belong you’re a tourist”. It is similar to saying, “This is 9 Mile Road [the Black community] and you don’t belong [because you’re not like us]”. He concludes his racial attacks by referencing sports ideally played by Whites and tells B-Rabbit to leave town.

B-Rabbit is stunned and faces a heckling crowd. They laugh in face and yell, “Choke!”. B-Rabbit does not say a word and hands the mic to Future. This withdrawal and defeat reflects the real life struggle Eminem went through while growing up in Detroit. As author Isabelle Esling writes, “During the time Marshall Mathers [Eminem] settled in Detroit, racial tensions divided both Black and White communities. A White kid wanted to rap faced a real challenge. Eminem’s road to success was far from easy. It required a lot of determination and drive” (Esling, ch.8, location 41).

By the end of the film, B-Rabbit returns to The Shelter for a second chance to battle the film’s antagonist Papa Doc and his crew, Leaders of the Free World. Again, B-Rabbit is caught receiving racial insults:

Fuckin Nazi, this crowd ain’t your type

Take some real advice and form a group with Vanilla Ice

And what I tell you, you better use it

This guy’s a hillbilly, this ain’t Willie Nelson music

Ill crack your shoulder blade

You’ll get dropped so hard

Elvis will start turnin in his grave

I feel bad I gotta murder that dude from “Leave It To Beaver”

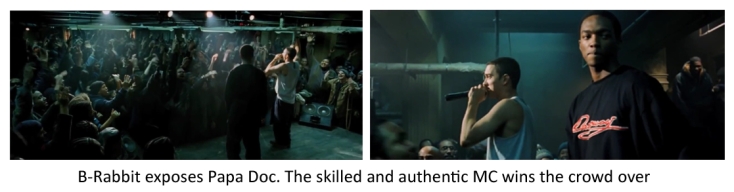

The lyrics use similar themes of race as the beginning of the film. The rappers scrutinize B-Rabbit for not being part of their crowd and compare him to White artists (Vanilla Ice, Willie Nelson, Elvis Presley). However, B-Rabbit retaliates with rhymes and lyrics that wins the crowd’s attention and offers an insight on MC’s and freestyle in Hip-Hop. Freestyle competitions, by this time, have become a complex art form with more sophisticated rhythms. While an insult needs to be clever and insulting, freestyling rhymes must be “dope” in order to be accepted by a Hip-Hop audience (Pihel 253). B-Rabbit’s winning freestyle battle was against Papa Doc and not only did he insult him, but B-Rabbit rapped about his own life. Again, as Murray Forman explains, space is a big factor in Hip-Hop. Space inspires an MC to tell stories that are true and authentic, resulting in a strong connection with an MC’s audience (Forman 95). B-Rabbit also puts Murray Forman’s perspective into his insults towards Papa Doc:

I know something about you

You went to Cranbrook, that’s a private school

What’s the matter dawg? You embarrassed?

This guy’s a gangster? he’s real name’s Clarence

And Clarence lives at home with both parents

And Clarence’s parents have a real good marriage

This guy don’t wanna battle, He’s shook

‘Cause there no such things as half-way crooks

He’s scared to death

He’s scared to look in his fucking yearbook, fuck Cranbrook

An MC moves an audience with words to “vividly depict contemporary life” (Forman, 95) and their artistic success credibility resides in their class and/or race relation (Hodgman 402). B-Rabbit is an example of class-based authenticity. He lives in a trailer with his single mother with financial issues and struggles to achieve his dreams while working at a factory. He removes Papa Doc of all credibility. He takes pride in exposing Papa Doc’s background who was supposedly a more authentic rapper than B-Rabbit solely because of his Black background. Papa Doc is speechless and B-Rabbit proves his authenticity – something he was criticized for solely based on his racial status.

B-Rabbit is now an accepted Hip-Hop figure in Detroit and will presumably become a popular one since the character is a reflection of Eminem. Because of this acceptance and popularity in Hip-Hop, author Scott F. Parker examines Eminem (and B-Rabbit) in comparison to Elvis Presley. Parker states that Eminem is the “Elvis of Rap” because he is a White man who “makes Black music credibly, creatively and compellingly” (Parker, ch.1, location 531). Eminem produces music that theorist Jefferey O.G Ogbar associates with African-Americans (Ogbar 12) and Elvis Presley became popular with R&B, another predominately Black world.

As Elvis did with R&B, B-Rabbit in 8 Mile challenges the racial ideologies of Hip-Hop which was made possible by the character’s authenticity and talent as an MC. With Murray Forman’s and Jeffery O.G Ogbar’s theories of Hip-Hop, I analyzed how the appropriate Detroit setting reflects B-Rabbit’s racial discrimination in a Hip-Hop culture that is predominantly African-American. B-Rabbit uses his environment to write and tell compelling stories through rhyme that moves an audience and proves his role as an MC. He won the Black audience over, similar to how Eminem (a reflection of the 8 Mile character) gained respect from his audience. Talib Kweli, for instance, is an American Hip-Hop artist from New York City. Kweli’s origins and race are authentic in reference to Jefferey O.G Ogbar’s Hip-Hop discussion: Hip-Hop was born from the expressive culture of the African-American’s with the children of New York City being the creators of the art (Ogbar, 12). Talib Kweli first witnessed Eminem battle in New York City and reminisces:

“I saw Eminem get dissed badly over and over again, mostly for being White, and then come back and obliterate his competition with the next rhyme. He did it every time. There were a few on his level, but nobody better” (Parker, forward, location 47).

This relates to B-Rabbit’s achievement in 8 Mile, a film that defines the Hip-Hop culture while challenging its ideologies. Going back to the discussion between B-Rabbit and his entourage of close friends, DJ IZ tells B-Rabbit, “There’s always room for a White man in a Black man’s world”. By the end of 8 Mile, DJ IZ’s opinion is realized.

Bibliography

Corrigan, Timothy. A Short Guide to Writing about Film. New York: Longman, 1998. Print.

Esling, Isabelle. Eminem and the Detroit Rap Scene: White Kid in a Black Music World. Phoenix, AZ: Colossus, 2012. Kindle ebook file.

Ferguson, Jordan. Donuts. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. Print.

Forman, Murray. The Hood Comes First: Race, Space and Place in Rap and Hip Hop. (Middle, CT, Wesleyan University Press, 2002). pp. 88-95.

Hodgman, Matthew R. “Class, Race, Credibility, and Authenticity within the Hip-Hop Music Genre”. Journal of Sociological Research. Vol. 4, No.2. pp. 402.

Ogbar, Jeffery O.G., Hip Hop Revolution: The Culture and Politics of Rap (Lawrence, Kansas, University Press of Kansas, 2007). p.p. 12

Parker, Scott F. Eminem and Rap, Poetry, Race: Essays. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2014. Kindle ebook file.

Pihel, Erik. “A Furified Freestyle: Homer and Hip Hop”. Oral Tradition, 11/2 (1996): 249-269.

Quispel, Chris. “Detroit, City of Cars, City of Music”. Built Environment (1978-), Vol. 31, No. 3, Music and the City (2005), pp. 226-236.

Digital Bibliography

8 Mile. Dir. Curtis Hanson. Universal Pictures. 2002.

“8 Mile (2002) – Box Office Mojo.” 8 Mile (2002) – Box Office Mojo. Web. 03 Nov. 2014.

A Hard Day’s Night. Dir. Richard Lester. United Artists. 1964.

Almost Famous. Dir. Cameron Crowe. Dreamworks Pictures. 2000.

Black Papillon. “Lil’ Tic Disses Rabbit”. Genius. Web. 20 Nov. 2014.

Ramirez, Erika (November 8, 2012). “Top 10 Best Hip-Hop Movies Ever”. Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Web. 03 Nov. 2014.

Walk the Line. Dir. James Mangold. 20th Century Fox. 2005.

XXL Staff. “Nas Says New York City Wrote Illmatic”. Theneeds.com. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

Images

8 Mile. Dir. Curtis Hanson. Universal Pictures. 2002.

Nas’ “Illmatic”

– – –

This is an essay examining the work of Hip-Hop artist Nas and his album Illmatic. While this seems unrelated to cinema, Hip-Hop is a culture that has been disseminated through film (such as 8 Mile, a film I also wrote an essay on which is posted right above this one!)

Author: Alberto D’Onofrio

– – –

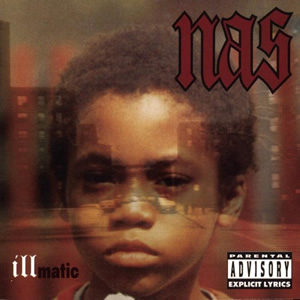

At first glance, Illmatic by Nas features cover artwork of an African-American child juxtaposed with a photograph of a street-block. The child is Nas himself, or more appropriately, Nasir bin Olu Dara Jones, at age seven (Cowie, 2) and behind the young boy is a gritty New York City block (Juon, 1). The significance of the photograph, especially at this early age, is explained by Nas in an interview with MTV: